The Intent Gap

Software testing can only prove the presence of bugs, not their absence.

This asymmetry limits how far we can scale. As software grows, each new component introduces failure modes that become impractical to detect by testing. This makes it difficult to ensure our intent is met. As a result, software engineering teams have come to rely on a complicated hierarchy of trust and best practices. But these only go so far.

The software we are building is made out of clay. Clay houses need constant maintenance, and can only rise so high before collapsing under their weight.1

What if there was another way?

Programming languages like Idris and Lean let you express your intent using code, then verify intent is satisfied by compiling. Let me show you what I mean.

Say you want to sort a list. In most languages, you’d write a function with a type like:

sort : List Int -> List Int.

The requirement that the output is sorted is left out, creating an intent gap: the difference between what you’ve communicated to the compiler and your actual intent. The compiler will reject your code if you return a string instead of a list, but if you return an unsorted list, it stays silent. This gap is why you need to test, because you know something you never told the compiler.

This is how most programmers have been taught to program. But type theory has advanced enough to change this.

In Idris, you can write

sort : (xs : List Int) -> SortedList xs.

Here SortedList xs includes not just a list, but a proof that the list is sorted.2

To implement this function you must have it return both the list and the proof.

The bug of returning an unsorted list is rendered impossible: the compiler will simply not let you run that program.

And if the compiler accepts your program, you don’t need to test whether your intent is met.3

If the specification matches your intent, there can be no bugs.

Languages like Idris and Lean make us rethink programming. Instead of writing code and then manually verifying it, you can now first encode your intent, and then implement it. The burden shifts from “does my code have bugs?” to “does my specification capture what I actually want?”. If it does, verification becomes mechanical: if it compiles, it’s correct. No testing needed.

Clay was eventually superseded by reinforced concrete, carbon fiber, and structural engineering. The reliability of these materials and the precision of our structural theories let us build things people a few centuries ago could not have dreamt of: space stations and rockets. Dependent types, through the same reliability and precision, will do the same for software.

So, what’s holding us back?

There are two things. First, specifying intent is hard. We often don’t know what we want. The process of writing code, like writing prose, reveals what we actually meant to say. True understanding of our intent demands deep introspection and emerges only as a result of it. This introspection is difficult to measure and incentivise.

Second, specifications have a surprising amount of detail. Take something as seemingly straightforward as database invariants: they require pages of mathematical scaffolding just to state the basics. Even with a PhD in the field, coding this up in Lean takes months of intense concentration. Under normal industry conditions, with tight deadlines and shifting business requirements, you seldom have that luxury. It’s much easier to just use MySQL and vouch to your boss that your implementation is correct.

For these reasons – because understanding intent is hard, and implementing it even harder – proofs have taken a backseat in mainstream programming. Humans prefer languages convenient to them, so these languages have proliferated. Languages optimized for correctness remain niche.

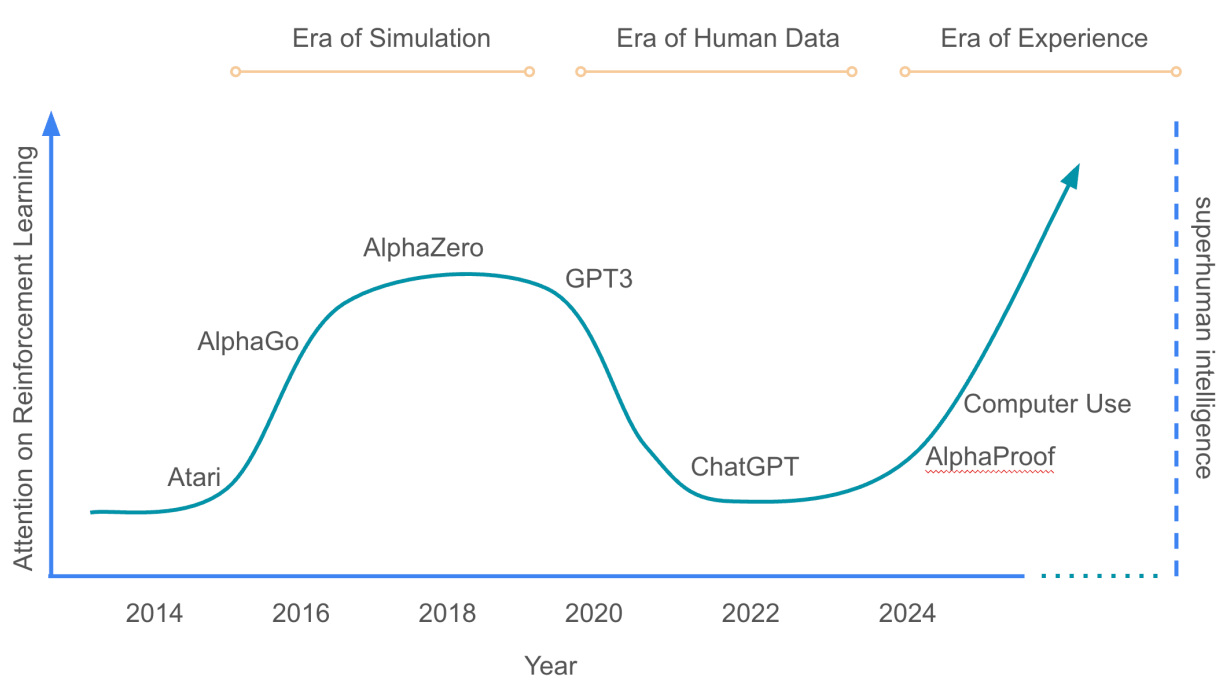

But that’s starting to change. We are employing AI systems to write more and more code, and these systems do not share our preferences. Are we sure AI will keep writing code in languages optimised for human convenience?

Just like new paradigms overturned the once dominant Cobol, the mechanics of scale and proofs will cause correctness-first languages to eventually overturn ones designed for human convenience. Just that this time, most of the code in the new paradigm won’t be written by humans.

We’re already seeing the beginnings. Transformer-based models are writing an increasing amount of Lean code, and helping mathematicians solve open research problems. While this is restricted only to theorem proving, it’s only a matter of time before it becomes clear that the same approaches are applicable to general programming. That’s when we’ll see the next AI wave: scaling software not at the expense of safety, but because of it.

Getting there, however, requires crossing some obstacles.

The fundamental obstacles is that of data. Transformer-based models excel in data-rich domains, but correctness-first languages are not one of them. These languages are concise by design: a few hundred lines of specification can define hundreds of thousands of lines of implementation. This makes them data scarce, starving LLMs of the training data. The Bitter Lesson in this case might actually be bittersweet.

There are also other, less-fundamental issues.

- Blindness to structure: LLMs treat code as an extension of natural language, lacking mechanisms to leverage its structure. Any structure that our code has – usually represented as an inductive, dependently-typed abstract syntax tree – has to be flattened into a linear representation before the LLM can consume it. And when producing outputs, they are always produced in a linear order, strictly autoregressively (left to right), without any ability to backtrack or change previous outputs: models are append only.

- Compiler integration as an afterthought: When LLMs generate code in dependently-typed languages, they do it vacuum sealed from the programming environment. They can suggest nonexistent imports, and call functions that do not exist. They can generate a hundred lines, only to be told by the compiler that there is an error on line one. That’s not how Idris and Lean programmers write code. They generate code step by step in a tight interaction loop with a compiler. The code that they wrote is elaborated, its full terms are exposed back to the programmer, who now continues to write code conditioned, and constrained by the type and structural information that they’d otherwise have to infer manually. Types aren’t used just to filter out invalid outputs, they’re used to help programmers reason. But output of existing LLMs is not conditioned on the existing proof state, nor constrained by it.

- Lack of infrastructure: Novel architectures, for instance those that produce correct-by-construction dependent types, are difficult to prototype when the tooling doesn’t support structure. Type-driven development and the level of generic programming possible in dependently-typed languages simply isn’t possible in Python. Building genuinely new architectures requires new tools, and those tools, such as automatic differentiation and tensor processing frameworks are missing from dependently-typed languages. Most attempts to build such tools only replicate what already is, without reimagining what could be.

These problems aren’t blocking. But solving them might unlock orders of magnitude more progress than pure scaling.

My research is centered on making that happen. I work on three fronts:

- New architectures: Understanding old, and designing new neural networks that natively consume and produce structured data

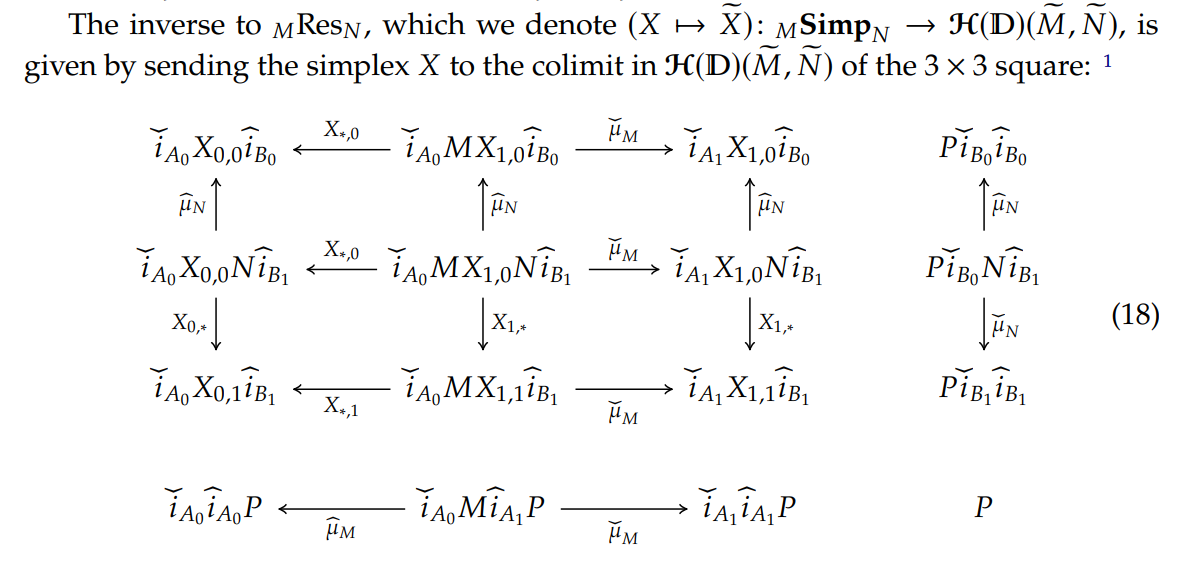

- Mathematical Foundations: Building the mathematics necessary to state precisely what it means to generalise, especially on data structures recursive in nature

- Infrastructure: Building the stack required to train such networks in dependently-typed languages: tensor processing, automatic differentiation and elaborator integration

In all of these, I use category theory, the mathematics of structure and composition, as a central glue.

Why category theory?

Because the organisational principles needed to build better AI systems turn out to be the same principles needed to build better programming languages, and to do science in general.

Any system that generalises well has discovered compositional structure in its domain. To generalise is to discover rules that apply parametrically, regardless of the size or shape of the input. And the more consistent and modular you make your rules, the more it looks like you’re following principles of category theory.

I suspect any sufficiently capable reasoning system has, whether by design or discovery, converged on these principles.

This raises a question: what might a formal theory of reasoning look like?

To answer this, it helps to look at how other fields found their foundations. Consider alchemy.

For centuries, alchemists mixed compounds through trial and error, chasing the elixir of life and panacea, the cure for all diseases. But this does not make alchemists bad scientists. It was the best they knew back then. Alchemists encountered new and unexplained phenomena, and made genuine discoveries. They discovered phosphorus, gunpowder4, and developed lab equipment. But because they lacked science, they couldn’t synthesise penicillin, build chemical manufacturing plants, or cure diseases at scale.

Something else was required. Over time, we discovered the atom. We built the periodic table. We understood the idea of molecules, bonds, reactions, and thermodynamics.

The result was chemistry, which is a completely different field. Chemistry is reliable, controllable, and scalable in ways alchemy never could be. We predicted new elements. We built petrochemical refineries, synthesised organic compounds, and unlocked the ability to capture carbon from the atmosphere. Today, we can actually cure many of the diseases alchemists were trying and failing to cure. But we do it in a very different way.

These are incredible advancements were not created by scaling up alchemy. They required that we discover fundamental principles first, and develop a whole new science: one unimaginable to alchemists.

Deep learning today feels like alchemy.

We’re making remarkable strides, and LLMs are impressive feats of engineering. But we have very little understanding of their internals. Nobody predicted phenomena like double descent, or the lottery ticket hypothesis – phenomena that seemingly explain a part of their behaviour. We’re collecting an abundance of experimental data, but in our pursuit we have not been able to glue it all into a cohesive theory.

In this pursuit, there is something self-referential.

To find a concise way to express how intelligent systems find good models of the world, it may be necessary to first reason better ourselves: to structure our own thoughts more clearly. If we are poor learners, we will not be able to describe learning well.

Category theory is a tool for learning. It’s a way to structure thought; one which is both general enough to allow us to reason about anything, but also one precise enough to prevent us from getting lost in meaning.

The ability to learn – intelligence – has often carried a mythical quality. Throughout millenia, it resisted precise formalisation alongside related concepts like consciousness, autopoiesis, and life. This was largely because the tools for formal specification were inadequate. But with the advent of 21st century mathematics, I believe we have the right abstractions.

At least, to ask the right questions.

Could category theory be the formal theory of reasoning we’re after?

I am a fan of the following quote from Bartosz Milewski’s book Category Theory for Programmers: “There is an unfinished gothic cathedral in Beauvais, France, that stands witness to this deeply human struggle with limitations. It was intended to beat all previous records of height and lightness, but it suffered a series of collapses. Ad hoc measures like iron rods and wooden supports keep it from disintegrating, but obviously a lot of things went wrong. From a modern perspective, it’s a miracle that so many gothic structures had been successfully completed without the help of modern material science, computer modelling, finite element analysis, and general math and physics. I hope future generations will be as admiring of the programming skills we’ve been displaying in building complex operating systems, web servers, and the internet infrastructure. And, frankly, they should, because we’ve done all this based on very flimsy theoretical foundations. We have to fix those foundations if we want to move forward.”↩︎

To sort a list

xswe need to provide a listys, together with proofs that the elements ofysare in ascending order, and thatysis a permutation ofxs. For details see this gist.↩︎You might ask: “What if the function sorts a list, but is not efficiently implemented?” In that case, your intent isn’t to sort a list, it’s to sort a list efficiently, and your specification needs to be refined. That is, the implementation matches the specification, but the specification does not match your intent.↩︎

Did you know that gunpowder was invented as an accidental byproduct from experiments seeking to create the elixir of life?↩︎